Your Party or Zack's? Two models of party leadership.

The left must choose between Corbyn's member-led dream or anoint Polanski their leader-saviour, both borne of Farage's success and Labour's toil.

This is one of two posts that mark my getting back to blogging. This a politics one and the other is a techy one, which very roughly are the dual themes of this new blog.

Funny how you wait your whole life for a competitive alternative to Labour and then two come along like buses. Perhaps it is a good problem to have, to be spoilt for choice when for so long we had none. But then there is the very real concern that a failure to rally behind one might spell disaster for both, squandering a once in a lifetime opportunity to reshape the electoral landscape.

To some extent ‘Your Party or the Green Party’ is the choice nobody asked for. The opportunity is the basically same for both: the broad electoral bases of Labour and the Conservatives have become unsustainable under the weight of historic political realignment, but have been propped up by an electoral and party system that confers on them a huge incumbency advantage. Fuelled by a confidence in this truism and the animosity of the 2017-19 civil war, Labour have relentlessly pursued the fraction of marginal constituencies that mark their frontline with the Tories and treated their own ‘core’ voters as an irrelevance, operating on the assumption that the electoral system would continue to gift them them those seats.

This was, until now, entirely rational — there really has been very little electoral incentive to court or even forgo antagonising the left. Until unthinkably, the inconvertible logic of the British two-party system finally cracked. Constituencies in London, urban centres and university towns which were once no-choice-but-Labour safe seats are now up for grabs. In a delicious irony for an embittered left, so safe were these seats supposed that many of those selected for them are now in Starmer’s top team and may have to fight to keep them.

I suspect most left-wing voters are not ideologically concerned whether it is Your Party or the Greens that contests them. The task is clear: to laser-target these seats with counternarratives on immigration, Palestine and redistribution, insurgency vibes, and exploit dissatisfaction with, and their distinctiveness from, Labour. The goal is a landmark result in May’s locals to secure further credibility as ‘real party’ and as the primary bulwark against Reform, teeing up a general election run where they take enough seats to force themselves into coalition with Labour, and establish themselves as a permanent feature of the British electoral map.

So which to choose? And why are there two options anyway? Interestingly, although Labour’s internal struggle has opened the floodgates for both of them, that struggle has also profoundly shaped one but not the other, and marks the only notable distinction between them.

The founding promise of Your Party is that it will be authentically ‘yours’, in the sense of being led by its membership. Ostensibly, it has no leader, Corbyn and Sultana only claimed they were co-leading the founding of the new party. Its six MPs have sought to position themselves as stewards of that party, the actual constitution of which will be determined through a series of regional assemblies and a founding conference in November. Both the roadmap to establishing the party and its core messaging (and the working title), put being radically grassroots, “doing politics differently – where decisions are shaped by all”, at the centre of the project.

It is also a logical product of Corbyn and Sultana’s last decade in the Labour Party. Corbyn was elevated to the top of Labour by the membership after Ed Miliband replaced the electoral college with a one-person, one-vote system. The shock election of Corbyn was not even met with the pretence of deference to the party’s democratic choice via this new method, but an immediate and bloody campaign by MPs and party officials to remove him, which failed but tarnished the party’s reputation. Under Starmer’s leadership, a new electoral system was approved with support of the unions and MPs, to their mutual advantage and at the expense of members, which would prevent another insurgency from the left.

So it is not much wonder, that Corbyn is attracted to the idea of a party that is member-led and incontrovertibly democratic by design. Such a party would be a permanent home for the Labour movement, from which they could not be evicted and would a enjoy greater consistency between ethics and electoral strategy. It would probably willingly re-elect Jeremy as leader, but assuming that is not a role he wishes to revisit, Sultana, the left’s next most visible figure, would be the presumptive frontrunner.

All this talk of likely leaders does somewhat detract from the point of Your Party however, which seems to be genuine attempt to move away from having a charismatic leader as the defining feature of a party’s public offering. The same cannot be said for the Green Party, which is moving in precisely the opposite direction.

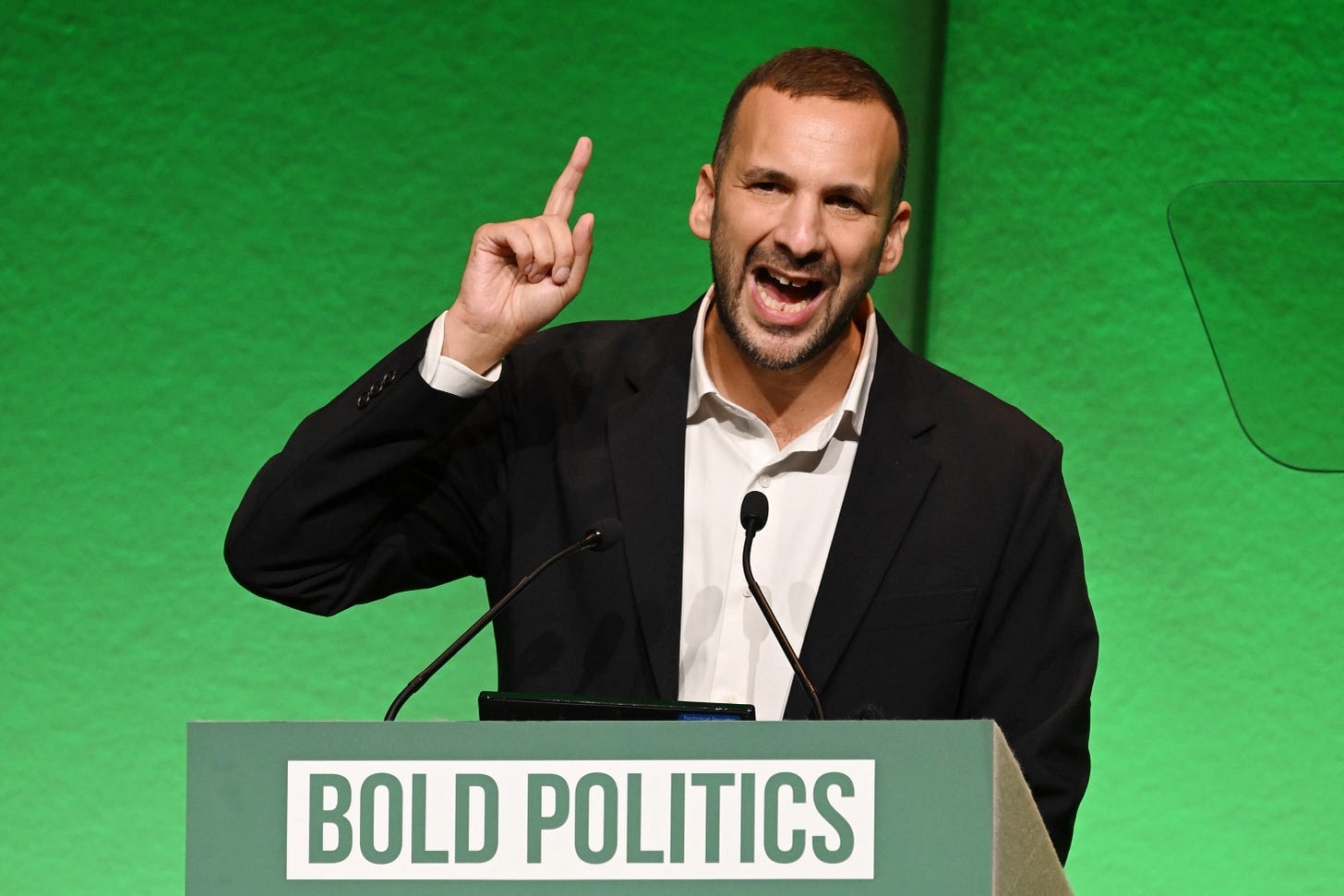

Until recently, the Green Party had two co-leaders, and an inspiring, pluralistic, nicey-nicey political innovation that was intended to reflect the party’s diversity and experiment with new modes of political leadership (presumably, it also doubled their capacity for appearances). The election of Zack Polanski over Adrian Ramsey and Ellie Chowns signifies two things. First, the decision to come out firmly on Labour’s left flank, rather as Ramsey and Chowns proposed, to build a larger, looser coalition incorporating other voters with which the party has made inroads, such as environmentally-minded centrists in rural constituencies.

Second, and as an extension of this choice to be a narrower, nimbler, insurgent left party, it signifies the party opting to revert to having a charismatic, conversation-leading, attention-sapping leader at the wheel. To start with, by electing Polanski the Green Party chosen to have a single face for the public to recognise. Beyond that, Polanski clearly has a way about him, and early doors his stock is appreciating fast. No doubt he is enjoying a honeymoon period, but he is also making timely and articulate interventions into public debate, is fashioning a clear direction for the party under his leadership, and marking it out as a clear alternative to Reform — and in the ability to do that, a clear alternative to Labour. The self-styled “eco-populist” has explicitly argued that the Greens should “learn” from Farage, which implicitly is saying ‘we should bet big on my personal powers of persuasion’. The effort to emulate Farage extends to selfie video monologues, a willingness to indulge in heated media debates and ploughing into difficult issues Labour would rather avoid. It’s hard not to see the logic of taking inspiration from Reform though, who are polling at 27%-ish at the time of writing, a limited company with no party infrastructure that is built entirely on the back of Nigel Farage’s personal brand.

This is the main substantive difference between Your Party and the Greens, one aims to be a democratic mass movement that generates an electoral proposition, while Polanski’s Greens aspire to orchestrate a mass movement through a skilful figurehead. Whilst the relationship between party and movement is old question for the left that long predates this moment, I suspect that most for now would be happy to support whichever was the most winningest. With that in mind, if there is another important difference between the two it is that the Greens are organised, established and on the up, while Your Party has managed to spectacularly implode before being founded.

I can understand why living and dying by the personal capabilities of a messianic leader doesn’t sit well with many on the left. But the debacle of Your Party demonstrates the contradiction at its heart and the necessity of some measure of hierarchical leadership: its founders wanted a party that would not be led by party elites, but it looks to be dead on arrival as a consequence of internal conflict between party elites over the direction the should take and who controlled various executive functions.

You can take the MPs out of Labour, but can you take Labour of the MPs?